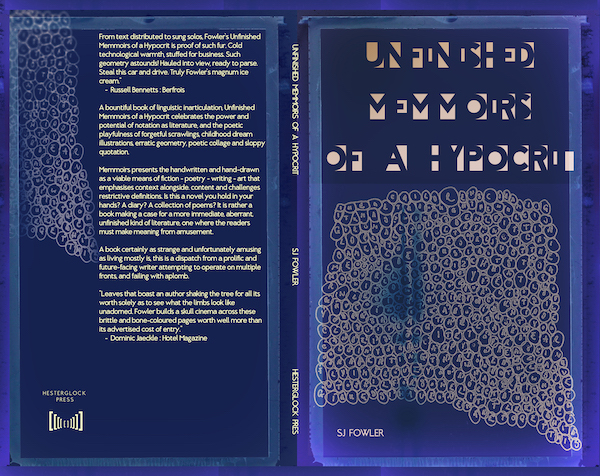

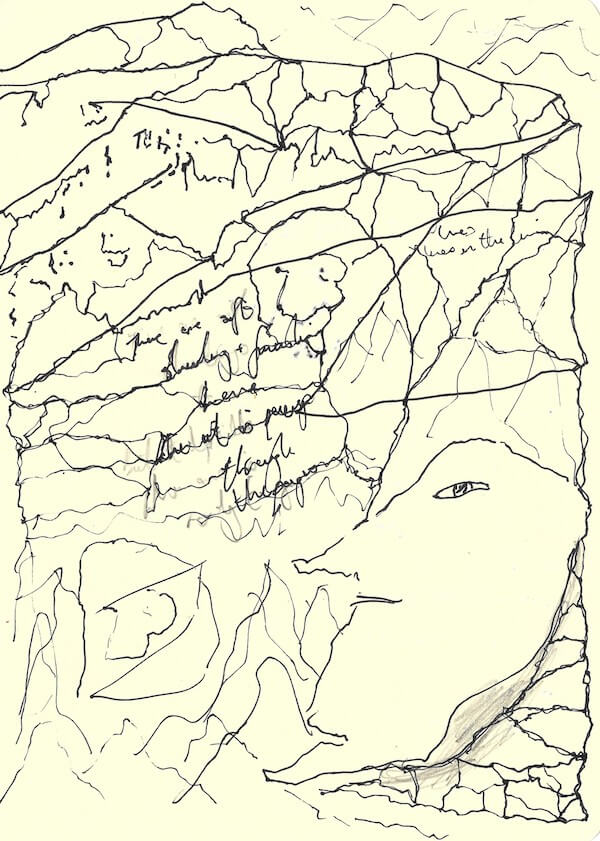

SJ Fowler shares his essay on the Unfinished Memmoirs of a Hypocrit (Hesterglock Press, 2019)

It has always been the custom for those who love Spain to abuse it.

– Gerald Brenan

Beauty is nothing other than the promise of happiness.

– Stendhal

It has taken me many years to know small things. It is my taste to feel that the most penetrating lyric, the most emotive poetry, is less meaningful than the misheard phrase or accidental utterance. The crafted insight of the lyric is a kind of bureaucracy, over flavoured, distant, protestant, clever without being intelligent. The unfortunate, the authentic unlearned, the bloody, often loud, is closer to my sense of things. I’d rather read a bad sonnet than a good one, if it must be a sonnet at all. Which it must not be. Have you been to a working class Spain without any English caffs?

I’m unwise to have not written several ‘topical’ books about what this book is about. It’s nearly 2020 and non-fiction sells so much more than fiction. Than poetry. Than avant-garde poetry. Than handwritten avant-garde poetry. Readers love real life stories. They love it when a writer turns their hobby into cash. I mean when they encounter expertise, at a specific word count, with a publisher they can trust, to a deadline, on a subject that was pitched and is of the moment. Yet, hypocritically, I try to keep hold of what it might look like for an author to not wish to please, to have their readers love them, or even like them. Is there a bargain to be made, without wanting to be obscure, to be so? To be dislikeable in one’s books in order to not be so outside of them?

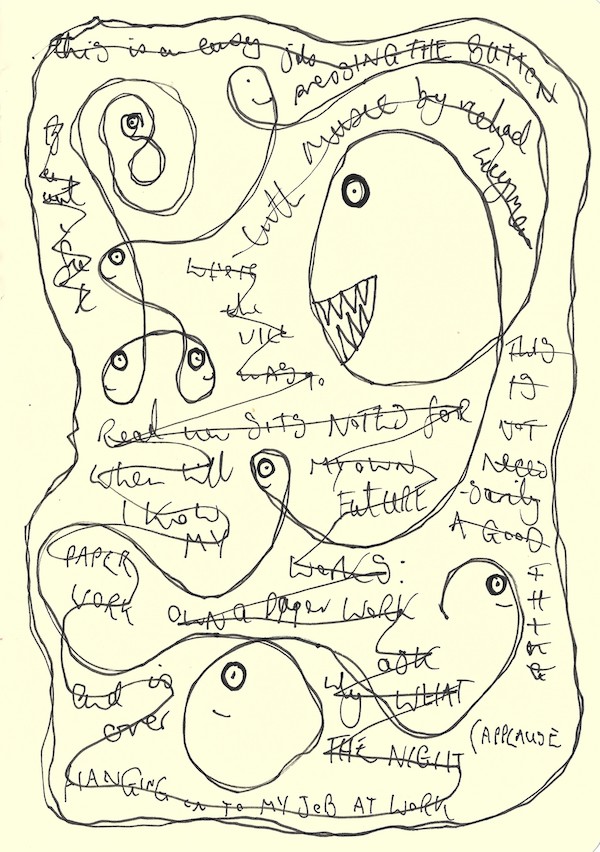

Every work is the product of multiple known and unknown influences. An entire book is then the product of an even more mysterious multitude of other extant sources and ideas and experiences. Often authors deliberate upon just the most obvious, that which has informed the content. Context – their style, whom they were reading during writing, where they wrote, how they wrote etc. – is secondary. This book is an attempt to emphasise the context over the content. To embrace it, knowing the result will be inarticulation and something unreadable by the standards of the expected, neat narrative poetry or prose.

The book is contextualised thus:

It was written using a single pen and a single notebook of a very distinct colour. Bone coloured paper. It was a Christmas gift from a family member who doesn’t know what poetry is. No work included was made without these two instruments.

It was written between December 28th 2015 and June 15th 2019.

It was ‘written’ directly after reading Stendhal’s ‘Memoirs of a Egotist’. Throughout the years since its beginning, I have made my way through every work I could find by the 17th French novelist. (Seek out Lucien Leuwen, parts 1 & 2 if you can, it’s his best and too little known in English). I realise an Egotist is not the same as a Hypocrite.

It was made almost entirely in Spain, and because of that country. Specifically, in Gandia, a provincial town bifurcated on the east coast, near Valencia - part seaside trap, part old world abandonment. This was the home city of the Borgia family.

It was made knowing it would be published, on sight of initial works, in early 2016 (I think), by my fellow poet Paul Hawkins, who runs Hesterglock press, out of Bristol, with Sarer Scotthorne. I knew it had a proper home, a place where it belonged.

It was made as part of an overall project I have been running, called Poem Brut, and would be a publication in a series I have been doing exploring poetry’s potentials. I knew it had a role in that project and in that series.

It had three different titles before this one.

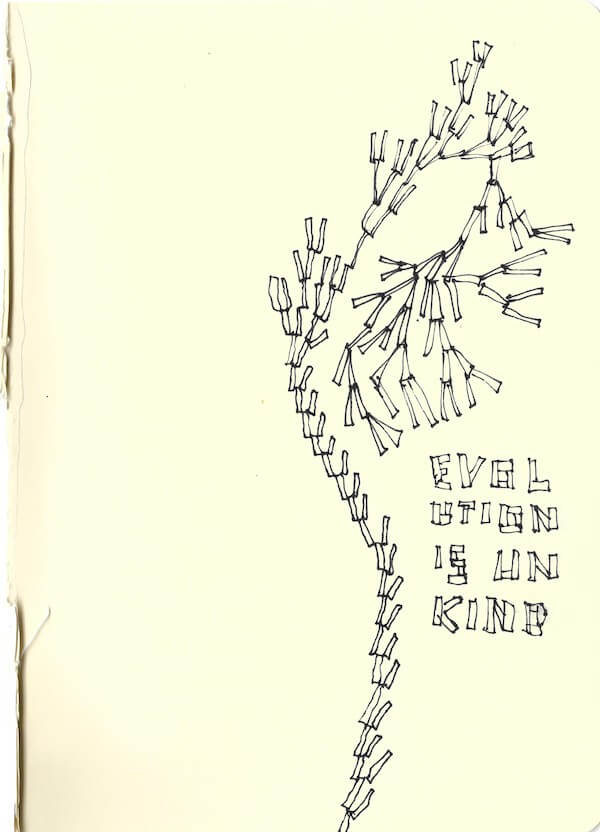

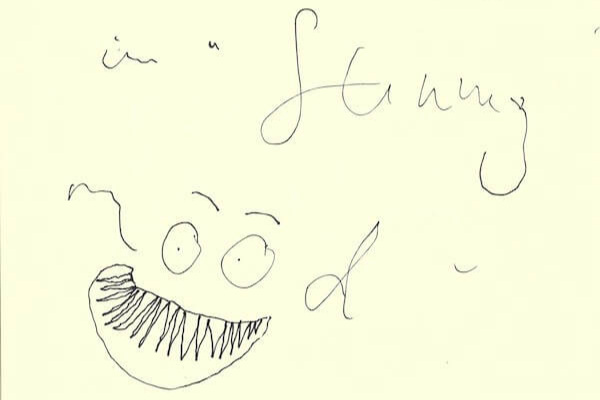

I was very taken also with book covers. My illustrations aren’t skilled, but I copied a few into this book, and this led me to other visual representations of existing artworks.

I was also reading William Golding, deliberately before I went to work at these, in bursts. I have family in Lyme Regis. He led me into Peninsula war history, Wellington biographies, rewatching. Sharpe.

I was watching the films of Peter Greenaway, trying to note them, translate them into notational poetry.

The book often touches on History and how impossible it is to be interested in British history without being seen as a bad person for not necessarily (though very often) making sweeping, simplistic, retrospective moral judgements on the past.

The work of the Spanish artist Mesa (there is copying here too). He is unknown in England, hard to find online, but I stumbled into an exhibition of his in Valencia and bought the catalogue and asked Spanish friends and was surrounded by details of his weird life and brilliant works.

Also the minimalist poem as slogan, with its knobbiness somehow deferred for being handwritten? The echo, the overheard saying, the slang, the noted, the forgotten. Fragmentary poetry that might have more than the finished. The book is forever unfinished, the works drafts, so why not the semantic content too?

The possibility of writing from pure instinct without the possibility of editing. Finality.

That’ll do. Though there’s lots more.

These are conditions of its creation and both the most essential and irrelevant information. These contexts are the best explanation I can provide on its content’s form and matter.

But let me explain further, with, first, a justification, or criminal defence. (I’ve been told often I’d better do this.)

First, the writing itself. The words are meant to make you squint, the other elements upon the page battle their legibility. Handwriting is an enormous source of visual information, all handwriting is signatory. I’ve been told I have nice handwriting. My father taught me. All things I write with my hand represent not only the paper and pen, those choices, but the essential, strange, ambiguous nature of my own penmanship evolving into a very specific set of marks, shapes, gestures and compositions. We have all heard of the somewhat apocryphal criminological technique of analysing handwriting. A kind of writing phrenology. Is this not poetic information? I believe it is, to be harnessed, to complement semantic content. And here is the obvious given of the handwritten, in the context of poetry anyway, it is visual as well as semantic. It operates on two levels. And at times, I push the words, making the writing abstract - pansemic or asemic, deliberately without semantic content, or with a volatility around the letters that means the reader has to complete or create them, subjectively in meaning, or see them, rather than read them at all. This is poetic, writing seen before it is read.

Somewhere in this book you can find sentences like your past is putting me in a funny mood and I’d rather not know.

You cannot always pinch and extend your thumb and forefinger against the page to get a closer look. I’m trying to scab the screens. I feel guilty about possessing my phone. Scribbling is correction without the initial connotation that blinds the true representation of experience and thought itself. As are crossings out, as are forgotten notes. As is the strange interaction between paper and pen. For it is strange, an insignia, a personal trace that has been relocated. Here are naff intersections between brutalism, poetry, handwriting and abstract illustration and as a major part of our day becomes how much time to spend online, while a movement slowly arises to disengage from online existence, so these works are meant to be a tiny return to the obscure, inarticulate, child-like intensity of the movement of the art brut and all it was influenced by. It’s more ambiguous than this, the meaning of the poems, but this is why it is deliberately rough, handworked.

At times the works explore ancient renditions of death’s reminders, at other times, geometry. Whatever was going. Whatever I was seeing, hearing, smelling, touching. Sex and the human form, collage, time, found language, the handmade, the amateur, the outside, the book is a tiny gesture of mine towards paint, ink and paper, towards liquid and wood, ugliness, toilet wall draughtsmanship and mess. They are a response to my being called an artist in the poetry world, and a poet in the arts world. All the materials – the paper, the ink, the paint – very carefully chosen (art paper, rollerball pen, soft pencil and children's fingerpaint from spain).

Somewhere in this book you can find quotations from the likes of Schopenhauer, Greenaway, Golding and Stendhal. But they aren’t accurate, and perhaps even apocryphal. Written from memory.

Next, Spain. The geometry of cold Spain. With a line the meaning of each letter ends, abrupt, load, looking you in the eye, but never fighting on Friday and Saturday nights. Screaming singing like a fight though. The specific spectres over this book are the city of Gandia and the artist Mesa, I’ve said, both of Spain as the wider ghost. If the ghost of this book had a nationality, it is Spanish. I wanted to avoid what English writers on Spain – Jan Morris, Gerald Brenan, Giles Tremlett … Rick Stein – have said. They are normally a bit cruel. Talking Labradors everywhere!

Lunch with my friends Marcus and Eva in the Agustin market in Madrid. I visit the bear at her tree in the plaza. I have a picture taken with a giant koala. Even in Madrid, the sky is larger, and the muted colours are younger and have softer edges. I stay in Toledo with a loved one. I ran the castle walls. They say the slopes were actual blood rivers during the civil war. It is unimaginable where we are.

This is a book about how it’s different to write a poem in Spain than in England.

In these endless corridors and courtyards you may sense the Spanish taste for the grandiose and the overbearing, fostered in the false dawn of an imperial prime, and often vulgarised in bombast.

– Jan Morris

English people in Spain are legion. Spanish poetry is not at all an influence on me. Especially now. One of the most conservative traditions and scenes in European, the formality betrays a deep insecurity and conservative lean. But this is because their light is so good! It’s no good for typewritten poetry. Suits the painter and handwriter better. All the same, in Spain, you cannot strike the keys twice. Typing is temporal, in time, like all else, but showing itself less than most other things. If you key the same poem twice over, by chance, in a bout of amnesia, say, in Gandia, say, there is no evidence that you did so, if the keyboard and programme is the same. Write that poem though, and it will be clear they exist independently, and show their age differently. The computer steals time in a country of immense light and unusual time.

In the coldness and bleakness of this building you may detect the aristocratic stoicism of Spain, something grandly ascetic in the character of the country, which often makes it feel otherworldly and aloof.

– Jan Morris.

Somewhere in this book you can find sincere gratitude. There is even a thank you to those who have helped me edit this very essay.

When I first seriously read poetry I did so in natural light, first from the monastic windows of Senate House in London, working in the evening, so always in there of a day, the thin slivers of normally concrete grey light cutting in to the old anthologies I would pour over, copying out lines from poems, without context, along with poets names, that caught me, often inexplicably, until I read them all back upon themselves. And then in Kensal Green Cemetery, where I would take single collections and read them entirely, as a kind of constraint, on park benches, surrounded by the dead and a few visitors.

What effect did that natural light have upon my reading, my understanding? Were I a painter, then this might’ve occurred to me then, and not now, reflecting, years in the future. Then I wasn’t aware whether I was reading differently in the light of day or under a bulb. What kind of bulb? What strength of light?

Writing too, then. But I didn’t type, I have so very often written out my poems by hand. I did so because I began writing while working at the British Museum, with no computer allowed, while on the galleries, guarding, but writing in a notebook. I was given all this back in the decaying urban Spain few English people have seen and I ended up within by chance, for stretches often longer than I wanted. This book is buried in that time too.

Somewhere in this book you can find Stendhal, who could never have understood Engerland.

This is the curse of our age, even the strangest aberrations are no cure for boredom.

– Stendhal

I know though, thanks to Stendhal, the world is littered with words. And often with books, that are testaments, that would change your life. But you never find them. And therefore you don’t find parts of yourself, littered. Probably true with people too. But with books, it’s obvious. For every book you discover you realise there thousands more you don’t. Who can pretend to have read a proper amount of books?

I felt very inspired by Stendhal because he created a literature because of his overwhelming self-awareness that represented that perceptiveness as a kind of romantic dissection of other people. You can notice too much, you can be too ready to see. He has taught me to not waste my time on certain suspicions, and as French as the French get, he also gave me a new Spain, a single notebook and a crappy pen I thought would long run out of ink before this book might end, and save myself and others from what this has not become.

Somewhere in this book you can find a skull, a monkey, a dirty tree, tears, a posterior presented, a goblin, a spider, a confession, a shark and a sun. In it monsters abound, and that seems true to me.

SJ Fowler, June 2019

Three poems from the collection are published in Tentacular here.