Three more practitioners respond to SLANT’s first event, Voiceworks

Calliope Michail

With you I am in that place, by LMB

In an open field, two bodies undulate together, they hug, they hold, they rock, they wrestle away. A memory - and it feels distant. In the foreground: the present, indoors and dark. A different kind of isolation. Leaning against a wall with the projected video behind them, the artists listlessly look off into different directions and speak over each other, repeating themselves, sustaining notes, buzzing, singing, humming. One of the repeated phrases is “I’d rather forget.” Memory becomes an irritation in the brain, a mosquito that keeps you hostage at night.

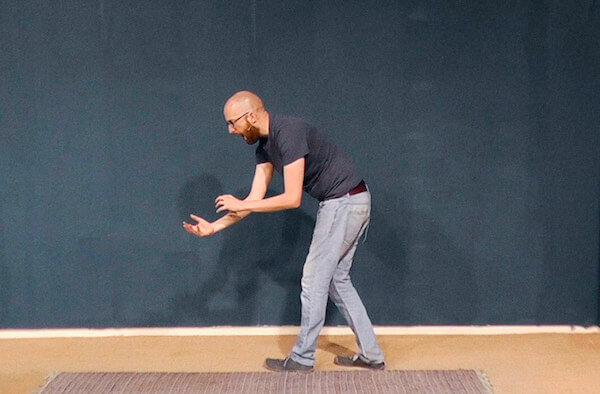

Incantation, by Richard Reynolds

A man stands alone. No visible paraphernalia, just his voice, with which he makes an array of sounds that electronically echo back – successive pizzicato bursts, longer vowels, pit patter and bass notes – and his bare hands, which appear to wield a magical power and control over an additional layer of sound. He holds, elongates, and releases it with the palm of his hand. This electronic sound extends into space, thicker than air. Sound becomes a tethered, kinetic, embodied experience. A mage’s dance with invisible threads and orbs sculpted through interaction.

You Cannot Forbid the Flower to Bloom, by Kinga Tóth

A white room. Cables, a log, a bowl, etc., are strewn around the artist who sits cross- legged on the floor with what looks like a large cellophane bundle of twigs in front of her. Her face is initially ‘sealed’ with tape. What follows is a chilling performance involving guttural sounds, moans, yelps, whimpers, interrupted breathing and other vocal and non-vocal sounds that are looped and unlooped to create a soundscape that evokes a deeply visceral reaction. This is a different side to embodiment. It is grating, a cacophonous lament, a struggle to break free... from something. She claws at the plastic wrapped twigs - is it suffocated human sized nest? “My mother My father!” Rubs the microphone against her throat. Water, bark, friction, sound and stone. You’re in a dense forest, winds blowing and it sounds like some creature is being devoured nearby. You feel an animal hunger to disobey. You cannot simply “stay and water the plants on the balcony” - though it may feel like a safer choice or is it a command?

Dylan Williams

In the last few months most of us have become even more reliant on technology as a way of keeping in touch with ‘culture’. It’s an irony, then, that this set of performances, most of which can be described as deeply physical and embodied, must come to us through the screens of our laptops and phones. It’s a testament to the forcefulness of these performances that they can force their way into our homes, without losing any of their energy.

Be it the frantic, absurd spellcasting of Richard McReynolds, or Serena Braida’s paralysing address in her piece ‘Oh You’. Or the aberrant energies channelled by Anamaria Burduli and Kinga Tóth. Or the yearning adjacencies of L M B’s performance, and the sensation of sheer disembodied blindness in Emma Bennett’s ‘The superficial front-facing way of putting it out there’.

The value of these strange, jarring broadcasts is their interruption of the airwaves in a time of crisis where language is instrumentalised to the point of torsion. A moment where language is bent into a tool to control thought and response. These six arresting encounters wake us up, invite us to think alone and in new collectives, about or languages, our bodies, about what is within our control, our lungs and our hearing, and what is not.

Hippolyte Broud

Reflection on LMB’s piece

They breathe and the noise is so loud, it’s as if the pulsations had to show us their metals. They are crimped with the most precious diamond. And the voices unfold: like prayers, like hymns, like sounds spat into the unknown.

Each sound is like short Iεροὶ λόγοι (hieroi logoi, ‘sacred discourses’) that would have been caught within the silence of the gods. Imagine Orpheus, coming back from the underworld. He has just realised that he’s lost Eurydice for a second time. He feels so talkative: he was forbidden to say anything for so long. And I am sure you know how difficult it is for a poet not to be able to blather their nonsense.

He wants to shout:

Euryidice ! Eurydice! Where are you Eurydice?

But he can only shout:

Are you there Echo?

And we can only hear:

Ouhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhh

Uhhhhhhhhhhhhhhh

Ouhhuhhhhhhhhhhhhhh

He is out of breath. He went to the edge of breath. He went to the edge of the constriction of the final asphyxia of the final dot of his final sentence. The state of exhaustion that precedes real meaning.

They play. It is like ‘a slap in the face of the unfulfilled dream.’ They tried Greek mythology and they cut their teeth on it. It gave them wings, the wings that the impossible gives to anyone who makes contact with it. And here we are: It vibrates, it flies in the ear. We listen to unpredictable vibrations. The image has left, the colours have left, and more important: WE are left without the image and the colours. And with barely any sound. There is just the murmur of the recording. It stammers, it tries to say something but it struggles.

When Orpheus, before his death, joined his singing to the chords of his lyre, he was still madly in love. He was still suffering. The memory of the passion had not yet been substituted for the passion itself. Yet Orpheus was at the beginning of his convalescence.

Reflection on Kinga Tóth’s piece

The voice suffers and this suffering echoes within us. The audience is like a wall. It can reverberate but it cannot share the sheer exertion of the voice. This is the voice of a body which wears away, which is crumbling while speaking. And while the body disintegrates, while it leaves its materiality in order to become a trace, it leaves space for a jungle of cries, a forest of screams, a wood of whimpers and whines, and a desert of music.

Never has eructation been so pernicious. It destroys everything in its path: it déracine the trees, it démembre the buildings. It empties the swimming pools from their waters and the bottles from their wines. The in-breath takes everything into its void: boys and girls, women and men, cats and dogs and so on and so forth. They all cry with the same intensity, with the same insanity to the extent that we can’t distinguish who is who anymore.

It seems that we will not be able to witness the last speech of humanity, as there is no speech anymore. Words are all gone, it is not a matter of language. The world will disappear without a last witty sentence, a last enlightening maxime from the langue de Molière. Sorry Louis, sorry Jean- Jacques: ‘Tout ça pour ça’. It is its organic form that confers its meaning to speech. An immanent meaning, which refers to nothing but itself, which can only be distinguished through a careful listening. The formation of speech requires an active participation from both the speaker and the listener. Together, they need to discern, within the sonic magma dozing inside the cave of their bodies, the formation of another organism. A little embryo who, like every embryo, is submitted to the rule of fate. Is it going to be voiced? Is it going to become a memorable parole or just one of these random words that everyone forgets right after they have been spat out?

But in this precise moment, the cave is crawling and the time to listen to the external world has gone. The baby won’t be born, he will be killed like everyone else, in the most excruciating pain. And sadly, no one will care. In these last minutes, speech is anecdotal, almost intrusive, even within the realm of voice. We are sounding beings but we become speaking beings. Speech is a precarious thing to acquire. It is never at the origin of all things, neither is it at the end of anything. It wanders and gets lost before life finishes.